The Art of Paying Attention

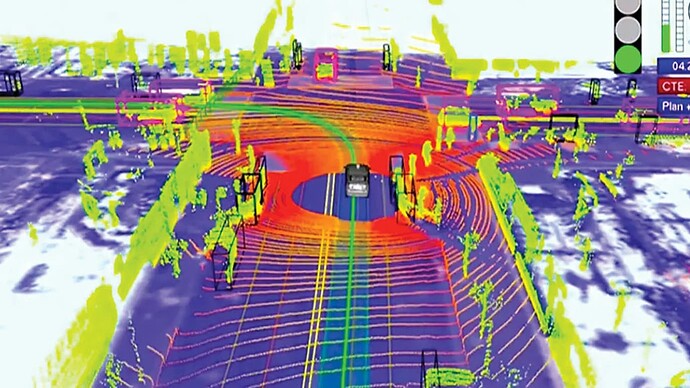

Last century robotics was plagued with the seemingly intractable problem of “seeing things”, a concept most humans take for granted. The catch for computers was they saw too much through the camera.

A scene generated by a robotic eye; BBC

The breakthrough came with the discovery that you only need to attend to important things and ignore everything else. Your own mind does this. Everything we see is converted into objects in a hierarchy based on what utility it has at that moment, everything else we just “don’t see”.

Imagine if you saw all things in your line of sight with equal importance. You would probably just kind of stop and cease to function.

So we taught robots to see like humans - that is, to recognise and prioritise objects. We spent a lot of time and energy teaching computers to pay attention to all kinds of objects even in very noisy environments. You might imagine the computer iteratively enhancing the image to better define the objects it’s looking for.

Humans like to day dream. We’ve all looked up at the clouds and seen the impossible; an elephant, a dancing rabbit, a sleeping giant and so on.

What if we gave the computer a very diffuse and noisy image like a cloud and told it to look for a rocket ship? Would it find one?

rocket ship emerging from a cloud; Midjourney

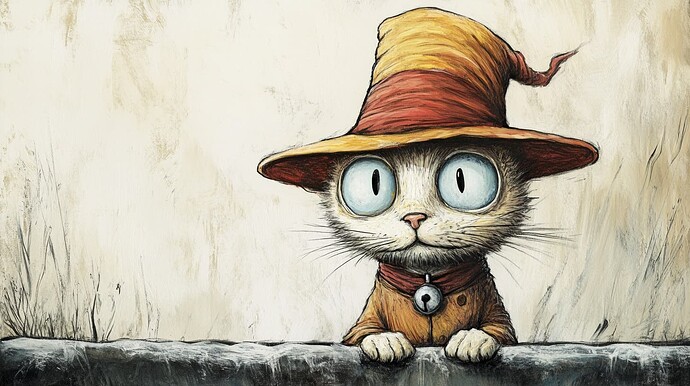

As it turns out, the answer is yes. After many iterations of enhancing and altering an image a rocket ship appears. And this turns out to be true of groups of objects; for example, a cat in a hat.

a cat in a hat by liniers; Midjourney

Breakthroughs in the last 10 years have enabled AI engineers to populate their data banks of recognisable patterns and objects from hundreds to billions.

With that shift in scale, something unexpected happened - without major changes to the core maths, there was a stunning improvement in image quality and sophistication. In the last 2 years, we have evolved from vague, blurry blobs with seven fingers to photo-realistic images rendered in seconds.

Here’s the rub

The recognition and composition of objects in an AI-generated image has little if anything to do with the final styling and texturing. “Style Transfer” is what gives the image its unique visual flair.

Much like the recognition of objects, AI models are also trained to recognise and resolve artistic and photographic styles, textures, colours and brush strokes to define a specific visual identity.

An artist’s name acts as an archetype or representation of stylistic elements that are statistically associated with that artist. The AI model has learned from many images labeled with that artist’s name or style, capturing the common features, such as brush strokes, colour palettes and compositional choices.

When prompted with “style by Van Gogh,” the AI doesn’t access specific paintings. Instead, it uses the artist’s name as a shortcut to a sub-set of stylistic patterns that define Van Gogh’s work; such as swirling brush strokes, vibrant colours, and thick textures.

Keywords like “Van Gogh” or “Impressionism” function as shortcuts for the AI to apply certain characteristics. There are a plethora of non-artist-specific keywords like “surrealism” or “minimalism” that can be used to guide the model to apply specific stylistic choices.

When you prompt an AI with conflicting style choices like “style by Van Gogh and Jeffrey Smart,” the model typically tries to blend the styles of both artists, incorporating distinctive elements from each into the final image.

For example, you might get an image where the expressiveness and bold colour palette of Van Gogh is applied to a scene with Smart’s characteristic sharp, clean lines and urban settings.

a cat in a hat, style by Van Gogh and Jeffrey Smart; Midjourney

The AI doesn’t “understand” the styles like a human would, but it does recognise the statistical patterns associated with each artist. Sometimes the styles will mix seamlessly for an interesting and surprising fusion, often times not.

Understandably, you can get a lot of rubbish results. The AI struggles with the concept of beauty, even more so than humans.

Or rather the rob

In art history, permission has never been required to emulate the style of prior art. Artists have always borrowed, adapted, and evolved styles as part of the creative process.

Current Copyright laws only protect specific works of art and not styles. Artistic techniques and aesthetics have always been considered part of the public domain. However, the emergence of AI-generated art has introduced valid concerns about whether the massive scale of style replication by AI should be treated differently than traditional human artistic influence.

So, should we treat AI-generated art differently when it mimics an artist’s style without copying a specific artwork?

Traditional emulation involves human creativity and intent. AI can mass-produce images in any style with limited human involvement and without consent. This feels very different from historical precedents.

But if the question is about the ethical use of artists’ styles how would you determine which artist owned a particular style?

Is any art truly original, or is all creativity just an evolution of what came before?